Amina's Voice Read online

For my father, a true gentleman, who is missed every day for his soft voice, intellectual curiosity, and generous spirit.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Writing Amina’s Voice also meant finding my own along the way, with the help of many special people. I’m enormously grateful to Andrea Menotti, friend, editor, and gifted storyteller, for launching me onto the children’s writing stage and continuing to guide me over the years. You are the best. I was fortunate to have talented author Naheed H. Senzai swap chapters with me during the first draft of the book and offer valuable insights. Two bright young reviewers, Jenna Din and Imaan Shanavas, gave me their honest assessments early on in the process. Afgen Sheikh was a huge support, as he carefully read each revision, talked me through my dialogue, and challenged me to make the story considerably better. My critique group, Laura Gehl, Ann McCallum, and Joan Waites, articulated what was missing in order to make Amina a stronger character when no one else quite could.

I want to express heartfelt appreciation for my agent, Matthew Elblonk, for believing in the importance of this story, and for working hard to find it a home. And a huge thank-you to editor Zareen Jaffery for both championing it and making it part of a groundbreaking effort in children’s publishing. I’m so proud to join the passionate team at Salaam Reads.

A number of other dear friends have cheered me on, listened to my whining, and celebrated my victories over the time it took to get this book published. You know who you are, and I couldn’t have done it without you. My parents and siblings always encouraged my writing, but my mother, Zahida Khan, is the one who instilled a love for books and reading in me at a young age. Everything I am is because of your tireless efforts. Finally, my husband, Farrukh, and two sons, Bilal and Humza, are my biggest fans and source of joy. Thank you for pushing me to pursue my dreams, for being patient with me, and for inspiring me every day.

1

Something sharp pokes me in the rib.

“You should totally sign up for a solo,” Soojin whispers from the seat behind me in music class.

I shake my head. The mere thought of singing in front of a crowd makes my stomach twist into knots.

“But you’re such a good singer,” Soojin insists.

I pause, enjoying the praise for a second. Soojin is the only one at school who knows I can sing, and she thinks I’m amazing at it. Every Tuesday we argue about the best contestant on The Voice and who deserves to advance to the next round. I can count on Soojin to end the conversation by saying that I’m better than most of the people on the show, and that I deserve to be on it someday. But what she doesn’t consider is that if by some miracle I was standing in front of the judges and live studio audience, I wouldn’t be able to croak out a word. I shake my head again.

“Come on, Amina. Just try it.” Soojin is a little louder now.

“Girls, is that chatter about you volunteering?” Ms. Holly stares at us from the front of the classroom with her eyebrows raised.

“Ouch!” I yelp. It’s Soojin’s pencil in my side again.

“Is that a yes, Amina? Should I sign you up for a solo for the concert?” Ms. Holly asks. “How about one of the Motown pieces from the 1970s?”

I sink lower into my chair as everyone stares at me and stumble over my words. “Um, no, thank you. I’ll just stay in the chorus,” I finally manage to mutter.

“Okay.” Ms. Holly shrugs, a frown clouding her face until Julie Zawacki, waving her hand like an overenthusiastic first grader, distracts her. Julie always wants the spotlight and tends to sing extremely loudly. It’s as if she thinks volume makes up for her lack of pitch. I always wonder how the math class next door gets any work done whenever Julie starts belting. But I still wish I had even half the guts she does.

“Remember, we’ve only got two months to prepare for the Winter Choral Concert. This is a big deal, guys,” Ms. Holly calls out as the bell rings and we file out for lunch.

“I can’t believe you didn’t sign up,” Soojin complains as we sit down at what has already become our usual spot in the lunchroom three weeks into the school year. “This is your big chance to finally show everyone what you’ve been hiding.”

I’m pretty sure that was what Adam, the judge with sleeve tattoos, said to the tall redheaded girl on The Voice last Sunday night, and I tell her that.

“I’m serious,” Soojin says. “It’s time to forget about John Hancock.”

Just the mention of that name brings back the memories I’ve tried to block since second grade: our class play about American independence. I was John Hancock and was supposed to say one line: “I will proudly sign my name in big letters.” But when it came time for the performance, I looked out into the audience, saw the sea of faces, and froze. There was this endless moment when the world grew still and waited for me to speak. But I couldn’t open my mouth. My teacher, Mr. Silver, finally jumped in and said my line for me, with a joke about how John Hancock had lost his voice but was going to sign his name extra big to make up for it. The audience laughed and the show went on while I burned with humiliation. I can still hear Luke and his friend jeering at me from the side of the stage.

“That was forever ago! We’re in sixth grade now. You need to get over it.” Soojin sighs as if my entire middle school future depends on performing a solo in Ms. Holly’s Blast from the Past production. I don’t let her see how much I agree with her and how badly I want the spot.

“Anyway, do you think I look like a Heidi?” she continues.

I have a mouthful of sandwich and stare at her as I chew, relieved that she’s changed the subject. I try to imagine her with a name I associate with Swiss cartoon characters or a famous supermodel—not my twelve-year-old Korean best friend.

“Not really,” I finally say after swallowing. “Why?”

“What about Jessica? Do I look like a Jessica?” Soojin picks carrots out of an overstuffed sandwich wrapped in white deli paper.

“No. What are you talking about?”

“I got it.” Soojin sits back and crosses her arms. She’s hardly reassembled her sandwich and it’s already half gone. No one I know eats as fast as Soojin. It’s one of the many ways we are opposites. I can’t ever finish my lunch, no matter how hard I try.

“What?”

“Melanie! I totally feel like a Melanie, and I love that name.” Soojin flips her long black hair off her shoulder and acts like she is meeting me for the first time. “Hi, I’m Melanie.”

“What’s wrong with you? Are you feeling okay?”

Soojin pretends to pout. “Just tell me, who do you think I look like?”

“Soo-jin,” I say slowly. I put the other half of my sandwich back into my bag and pull mini pretzels out. “You look exactly like a Soojin.”

Soojin sighs again, extra loudly, just like she does when her younger sister pesters us to play with her. It seems like I’m getting that sigh more and more lately—ever since the start of middle school. “That’s because you’ve always known me as Soojin, Amina.”

“Yeah, that’s my point.”

“What’s your point?” I hear a familiar voice behind me and turn around. A small, blond girl is carrying a cafeteria tray and a jumbo metal water bottle with the words “I am not PLASTIC” on it. Emily. Her green eyes and tiny nose remind me of my next-door neighbor’s bad-tempered cat, Smokey.

“Nothing,” I say. I wait for her to keep walking to the other side of the lunchroom, where she always sits with Julie and her crew.

“What are you guys talking about?” she asks.

I wait for Soojin to answer, expecting her to say something to send Emily scurrying. Even though the cat gets my tongue when either Emily or Julie come prowling, Soojin never has any problem telling them exactly what she thinks.

But Sooji

n just says, “I’m thinking of new names for myself.”

“New names? That’s weird. Why?” Emily starts a stream of questions. And as much as I want Emily to leave, I want to hear the answers.

“It’s not weird at all, actually. My family and I are becoming citizens soon, and I’m going to change my name.”

“Wait. So that means you’re not even American?” Emily sounds offended.

“What?” I ask. There is no way I heard Soojin right. “Change your name? What for?”

Soojin smooths her hair, sips some fizzy juice, and takes a deep breath. “We moved from Korea when I was four, and we aren’t American citizens yet. But we are about to be, and I’m going to change my name. I just haven’t picked one yet.”

“Oh, I have the perfect name for you,” Emily volunteers. She plops down her tray on the table and smiles like she is about to spill a juicy secret. “Fiona,” she says.

“Fiona?” I snort. “As in the green ogre girl from the Shrek movies?”

“No. Fiona, as in my uncle’s Scottish girlfriend. She’s totally pretty.”

I flash Soojin a look, but she doesn’t notice. Instead, she actually seems to be pondering the name as if it’s a possibility. An ogre name! Suggested by Emily!

And then Emily suddenly starts to shove herself into the space next to me. I don’t move at first. But when she’s nearly in my lap and Soojin still doesn’t say anything, I scoot over to make just enough room for her. Then I lean across the table and stare hard at Soojin.

Why is Emily sitting with us?

Ever since before Soojin moved to Greendale from New York in third grade, Emily has worked extremely hard to be Julie’s best friend. Mama would say Emily was Julie’s chamchee, which means “spoon” in Urdu. That doesn’t make a lot of sense, except that it also means “suck-up.” And Emily has always sucked up to Julie, even if that means laughing really hard at her dumb jokes or chiming in when she puts everyone else down. And by everyone else, I mean mostly Soojin and me.

“Fi-oh-na,” Soojin repeats. “That’s kind of nice.”

“Do you like it?” Emily asks me.

“Not—um—I don’t know,” I stammer. “Do you seriously think she looks like a Fiona?”

“Duh. She can look like anybody she wants, can’t she?” Emily turns back to Soojin.

My face grows hot.

“Don’t you like being Soojin?” I ask my best friend in a low voice, leaning across the table to make it harder for Emily to hear. “You’ve been Soojin your whole life. Aren’t you used to it?” I want to add that we had always been the only kids in elementary school with names that everyone stumbled over. That is, until Olayinka came along in fifth grade. It’s always been one of our “things.”

“Really, Amina? I thought you, at least, would understand what it’s like to have people mess up your name every single day.” Soojin lets out her sigh again. And this time it feels like I deserve it, even though I don’t know why.

Mama told me once that she picked my name thinking it would be easiest of all the ones on her list for people in America to pronounce. But she was wrong. The neighbor with the creepy cat still calls me Amelia after living next door for five years. And my last name? Forget about it. I could barely pronounce Khokar myself until I was at least eight. And since I don’t want to embarrass anyone by correcting them more than once, I just let them say my name any way they want.

Soojin is the only one at school who gets it. Whenever a substitute teacher pauses during roll call and asks, “Oh, ah, how do you say your name, dear?” I don’t even have to look at her to know she’s rolling her eyes. We still collapse into giggling fits if one of us mentions the lady who called me Anemia, as in the blood disorder. But now all of a sudden Soojin wants to be a Fiona or a Heidi?

Does it have something to do with being in middle school?

“What other names do you like?” Emily asks. She’s so interested in the conversation that she hasn’t touched the limp grilled cheese sandwich on her tray yet. I lean back and chew my pretzels while Soojin repeats her other choices to Emily.

“Ooh. I like Melanie, too,” Emily says. As I watch them chat, the lunchroom starts to feel like someone’s cranked up the heat. My palms get sweaty, and I feel super thirsty, and not just from the pretzels. I look around and find Julie sitting at her usual table, talking with a couple of new girls from another elementary school. She doesn’t seem to even notice that Emily is missing. I don’t say another word until Emily gets up to put her tray away and go to the bathroom before the bell rings.

“Soojin’s a pretty name too,” I say in as normal a voice as I can. “And I’m not just saying it because I’m used to it.” I want to add that I can’t imagine calling Soojin any of those other names, and that it would feel like I was talking to an impostor—but I don’t. It doesn’t seem like Soojin wants to hear that.

“Thanks.” Soojin’s face softens. “You know, a lot of Korean people have two names, a Korean one and an English one.”

“Yeah. But you didn’t have another name before. So why do you want one now?”

“I always wished I had a different name. Besides, my whole family is picking new ones.”

Soojin’s dad already goes by George and her mom is Mary, so their names would just become official after they take the oath to become citizens. I call them Mr. and Mrs. Park anyway, since my parents never let me call any grown-ups by their first names. Everyone is Auntie and Uncle or Mr. and Mrs. But Soojin taking on a new name just doesn’t seem right.

“Can I still call you Soojin?” I ask after swallowing hard to clear the lump that has formed in my throat.

“I want everyone to use my new name and get used to it in middle school, so it’s normal when we get to high school. It would be messed up if my own best friend didn’t do it.” Soojin peers into my face expectantly. “You will, right?”

“Yeah. I will,” I promise, although I cross my toes inside my shoes. I decide I will call her Soojin for as long as possible. The knots tighten in my stomach again, churning the half sandwich, seven mini pretzels, and three bites of cookie sitting inside. I watch Soojin put her empty containers back in her lunch bag, looking for a clue to why she’s acting so bizarre. Because even though I can’t explain why, something about Soojin wanting to drop her name makes me worry that I might be next.

2

I spot Baba’s car pulling up outside the music school building and stuff my song sheets into my folder.

“You nailed it, Amina. We’ll pick a new song next week,” Mrs. Kuckleman says. Her face has been smiling for the past six years that I’ve been pounding on the yellowed keys of the Tony Fritz Music Center’s piano every week. It wasn’t long after I started lessons that Mrs. Kuckleman told my parents that I have perfect pitch, since I can recognize any musical note. They were overjoyed—especially Baba, who loves the word “perfect” when it applies to his kids.

“How’s my geeta?” Baba asks as I scramble into the backseat before the car behind us has a chance to honk. My father says he calls me geeta, or “song,” because even my newborn crying was to the theme of his favorite Bollywood movie, Kuch Kuch Hota Hai.

“Really hungry,” I say. “Where’s Mama?”

My mom usually picks me up, since Baba’s schedule is so unpredictable.

“She’s at your school for the back-to-school night. We are going now.”

“We? I’m not supposed to go! It’s only for parents. Can’t you drop me home first?”

“No, no, there’s no time.” Baba shakes his head. “It’s fine. You can wait in the hallway.”

I want to explain to my father that it would be completely embarrassing to be the only kid tagging along with her parents at back-to-school night. But he would just say, in the Urdu accent he hasn’t lost after living in the Milwaukee area for twenty years, “Embarrassing? I don’t understand this embarrassing. Why do you care what people think?”

“It’s okay. You don’t have to go. Mama’s alrea

dy there,” I plead. “You must be tired.”

“Your mother wants me to go. And there’s only half an hour left. It’s settled.”

I don’t argue further and sink into my seat, glad for a change that Baba doesn’t allow me to sit in the front so I can sulk in peace. I’ve been begging him to let me, since I’m turning twelve in five months, but he hears too many stories about air-bag disasters from the trauma team he works with at the hospital. And since I haven’t reached the recommended minimum age on the air-bag warning sticker, and since I barely weigh eighty pounds, I’m lucky he doesn’t force me into a booster seat.

We get to school in time for the last three classes, since there are only ten minutes allotted for teachers to summarize their lessons. By the last session, I honestly don’t know who’s wishing more that we hadn’t shown up—me or Mrs. Gardner. Maybe Baba is trying to make up for being late, but he won’t stop asking questions.

“So these experiments, will they include lab work?”

All the other parents are shifting in their seats and checking their phones. I look at Mama, trying to will her to control my father. But Mama is beaming with pride over her husband’s interest in my education.

“And that wraps up back-to-school night,” Mrs. Gardner finally says after answering Baba’s last question and ignoring him when he raises his hand again. “Thank you for coming. We’ve had a successful first three weeks of school. If you have any other questions, please e-mail me.” Then she hurries to the back of the room, grabs a bag from the closet, and ushers us out the door.

“Your teachers seem nice. But it sounds like you’ll have a lot of work,” Baba says on the way home. He pulls into the driveway and turns around to face me, dark eyes serious. “You must study very hard in middle school. You see what happened to your brother?”

“I know, Baba.” My older brother was a star student in elementary school. But once he got to middle school, Mustafa’s grades went downhill. Since he started high school this year, dinner often becomes lectures about how Mustafa needs to “get serious.” And a few nights ago, when they thought I was in bed, I heard my parents talking about him getting “out of control like those American boys.”

Amina's Voice

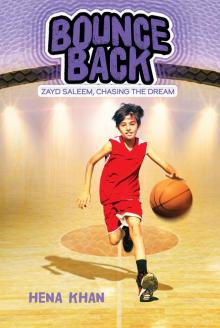

Amina's Voice Bounce Back

Bounce Back